This article was updated on 23 February 2025 to take account of the development of our new site which dynamically analyses the Biodiversity Gain Register and collates and summarises the published data:

To date, 46 of these biodiversity gain sites (BGS) have been registered in England. They provide:

- 1,376.7 hectares (ha) of baseline area habitat.

- 32.76 kilometres (km) of baseline hedgerow habitat.

- 11.37 km of baseline watercourse habitat.

The BGS sites cover 1,770.41 ha, though not all of this area is used for habitat improvement. 1,420.83 ha baseline habitats are made available for offsetting habitat loss caused by development elsewhere where this lost habitat cannot be replaced on the development site itself.

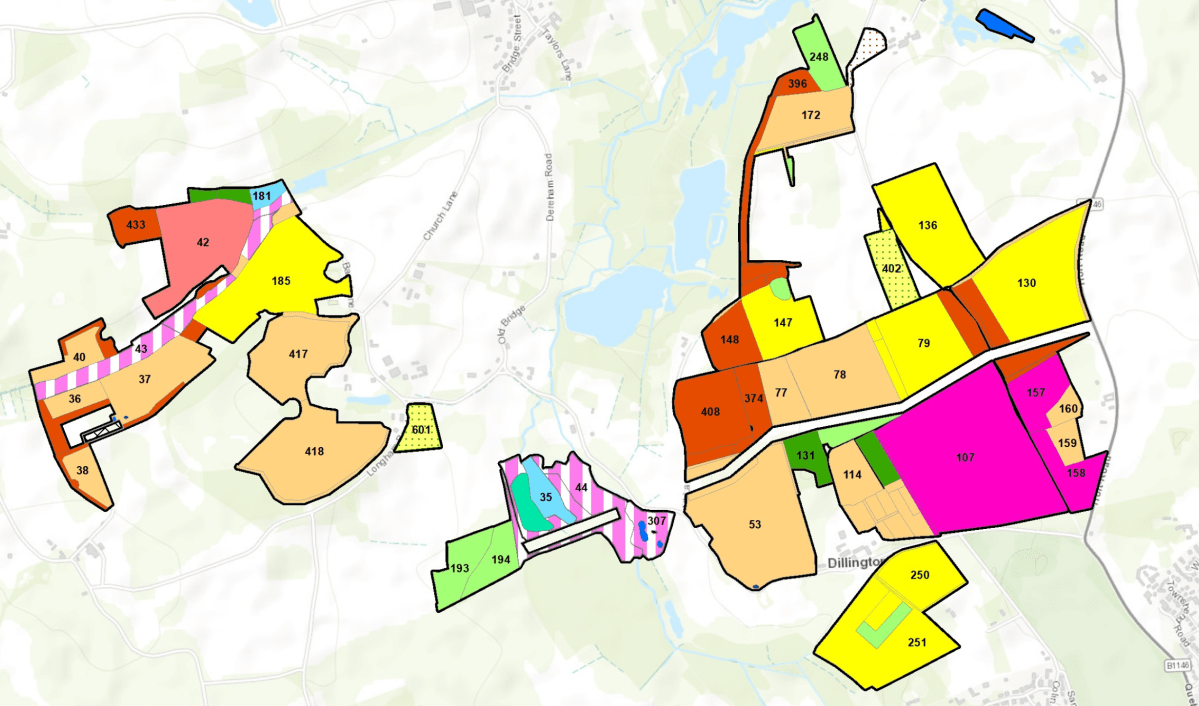

Distribution of biodiversity gain sites in England

19 of the 46 BGS sites are controlled by RSK Biocensus Limited as the Responsible Body but are mostly owned by Environment Bank. One other is controlled by Harry Ferguson Holdings (based on the Isle of Wight) as the Responsible Body, with the remaining sites under the control of various Local Planning Authorities (LPA) as the Responsible Body. We assume that the LPA sites have been created in order to deal with those local developments which require offsite mitigation. Nonetheless, these sites are also selling habitat to developers which require offsite mitigation but are outside the LPA boundary.

We also ask who is policing these sites to ensure that was has bee promised is being delivered? This must especially be the case for LPA sites given that the LPA cannot monitor itself?

In Bristol the LPA has delegated this function to neighbouring authorities using s.101 Local Government Act 1972 (the power for councils to delegate functions to other local authorities). – See 30 Sept 2024 Economy and Skills Committee notes – from paragraph 9. It will be interesting to see how this turns out. However, despite this, no BGS sites have yet been registered in the city, so it is hard to see how this initiative will be delivered where offsite mitigation is required.

The habitat improvement potential

These sites provide a total of 4,819.3 area baseline habitat units (HUs), 325.59 hedgerow baseline HUs and 105.6 watercourse HUs – we have assumed that all the sites have low strategic significance and that the watercourse habitats are free of encroachment.

We have been able to calculate the improved habitat units being created but not the improved habitat units being enhanced. This is because the parameters upon which these baseline habitats are being improved have not been identified.

The take up to date

So far, 31 of these 46 BGS sites have been used by 59 LPAs to allocate lost habitat caused by 85 developments. The majority of habitats are Other neutral grassland and the remainder are Lowland meadows, Traditional orchards, Floodplain wetland mosaic and CFGM, Mixed scrub, Woodland and forest and Hedgerow habitat.

To encourage developers to choose sites as close as possible to the habitat loss, they don’t need to pay a ‘spatial risk’ penalty if the biodiversity gain site is within the same Local Planning Authority (LPA) as the development. However, if the biodiversity gain site is outside the LPA for a particular development, the developer must pay a penalty when calculating the number of habitat units to be offset. If the site is in an adjacent LPA, the penalty is 25%. If it is farther away, the penalty is 50%.

Unfortunately, it appears that developers are not using BGS within their LPA areas (if available) for offsetting but are paying the spatial risk premium, though perhaps this is because they have no choice as there are no local BGS sites available.

Our analysis shows that, to date, the average distance between the centre of the LPA* where the habitat was lost and where its loss is offset is 80.1 km, with the greatest distance between loss and replacement being 344.8 km. Only six sites are within 10 km of the site of the habitat loss, while 23 are over 100 km away.

* It is difficult automatically to calculate the exact site of the habitat loss on the basis of the information provided. If at least Post Codes were provided, this would be possible.

What is particularly notable is that many of the development sites we have examined appear to be in locations where there should be ample opportunities for local habitat to be improved, but nothing has been done to realise this. Even the South Downs National Park LPA has allowed the replacement of habitat lost in two applications on the same site under its care near Petersfield to be exported to a site some 67 km away near Lewes, albeit that it is still in the National Park.

Furthermore, all 46 of the BGS sites are located on private land, in rural settings that are not easily accessible, whereas the lost habitats were largely located in built-up areas.

However, given the requirement that offsite mitigation only be delivered on registered sites, its hard to see what choice developers have apart from testing the BGS market and buying the cheapest habitats required, albeit that this may be miles from the site of the original loss.

This is still a small sample, which will grow over time so, perhaps this will change as more biodiversity gain sites become available and a clearer trend emerges. At the moment, however, the trend is not encouraging and looks like it will result in local nature, especially in urban settings, becoming hollowed out, as we feared it would when the biodiversity net gain requirements became obligatory nearly a year ago. See our article on this: ‘It seems inevitable Bristol will see a steady, inexorable biodiversity decline’