Dear Councillors

The Mayor has now published the next iteration of the proposed new Local Plan (LP). This will be brought before you at Full Council on 31 October next. The Mayor recommends (item 8) that, under Regulation 19 of the Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012, the draft LP will be formally published in order for representations to be made and then submitted to the Secretary of State for examination.

The sustainability appraisal documents are published on the Local Plan Review web page.

In our opinion the proposed LP is not yet ready for further consultation, let alone independent examination, for the following reasons:

- It does not contain enough detailed information about the sites in the adopted LP to allow for a proper consultation or independent examination.

- Protection for green spaces has been reduced, contrary to adopted Council policy.

- Despite the recent Ecological and Climate Emergency Declarations, this draft provides fewer environmental protections than the adopted LP.

- Comments on earlier drafts appear largely to have been ignored, rendering the consultation process flawed.

Our response in detail

Section 20 (2) of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 states that the authority must not submit the proposed LP unless they think the document is ready for independent examination. In our view, the proposed LP is not yet ready for further consultation, let alone independent examination. Our reasons are set out in detail below:

A proper consultation has not been conducted. In a 2001 judgement Lord Woolf defined a proper consultation as containing four elements.[1] The final element is that ‘the product of consultation must be conscientiously taken into account when the ultimate decision is taken’. You have not responded to our carefully considered comments on both the 2019 and the 2022 consultations on earlier drafts of the LP and there is no evidence that the Local Plan Working Party even discussed them. We do not know how many other organisations who submitted comments were also ignored, because these have not been published.

- When the 2019 document, New Protection for Open Space, was published for consultation, a schedule with maps was produced so that consultees could see which sites were being proposed and with what designation – Local Green Space (LGS) or Reserved Open Space (ROS). No such document has been produced in this version, which means that there is no easy way for consultees to see what has been changed, added or removed – save for slavishly working though the only document showing the new designations set out in 08.3 Appendix A3 Policies Map. Whilst this may be sufficient for those interested only in the information at ward level, it is nigh on impossible for those with a city-wide interest.

- An interactive GIS map of the proposed Bristol Local Plan Policies Map should be made available to facilitate examination. The pdf version provided has 38 layers in the Key and many sites have multiple designations, which makes it very difficult to interpret. The current Local Plan Policies map does this.

- Whilst the document Appendix 3 Assessing the effects of the Publication Version Policies, cross-references, to a limited extent, how some proposed new policies relate to policies in the adopted LP, there is no equivalent schedule for the adopted policies which will be removed – Core, Site Allocation and Development Management Policies (SADMP) and ancillary Supplementary Planning Documents (SPDs) etc. – nor any comprehensive cross-tabulation showing which of the adopted LP policies have been transferred to the proposed LP and which have not.

- No schedule has been prepared showing those sites protected under the adopted LP and whether they will be protected under the proposed LP. For example, SADMP DM17 currently provides protection for sites designated as Important Open Spaces, Unidentified Open Spaces and Urban landscapes. It appears that DM17 will be removed but that these current protections will not be adopted in the proposed LP. We have mapped 523 Important Open Space sites covering over 2,000 hectares. As far as we can see, some 1,000 hectares of these and all Unidentified Open Spaces and Urban landscapes, will no longer have any protection. If this is the case, then the proposals should make this clear. Our recent article, Will Councillors Honour Their Promise To Protect Bristol’s Green Spaces? addresses our wider concerns.

- SNCIs are currently given protection from development under SADMP DM19. This states that ‘Development which would have a harmful impact on the nature conservation value of a Site of Nature Conservation Interest will not be permitted’. It is proposed that DM19 will be removed in its entirety. Under proposed new policy BG2: Nature conservation and recovery, this protection has been changed to read: ‘Development which would have a significantly harmful impact on local wildlife and geological sites, comprising Sites of Nature Conservation Interest (SNCIs) and Regionally Important Geological Sites (RIGS) as shown on the Policies Map, will not be permitted.’ This is a dilution of the current protection enjoyed by SNCIs (and RIGS); the phrase ‘significantly harmful’ is a subjective judgement and undermines the current protection provided, especially when the Chief Planning Officer has recently advised Councillors that damage to an SNCI which is offset by onsite mitigations under the Biodiversity Metric is not harm.

- Whilst we are very pleased to see that our campaign to have all those Sites of Nature Conservation Interest (SNCIs) which were allocated for development in 2014 (save for BSA1305 – why?) has succeeded and have had their Site Allocations removed, we are concerned to note that not all of the 108 sites (not 85 as is wrongly suggested) have also been designated as LGS – some are ROS and some have no designation at all. No explanation has been given for this.

- No schedule of the sites identified in BG2 has been produced. As we have pointed out, there are 108 SNCIs, not the 85 stated in Appendix 1: Sustainability Appraisal Updated Scoping Report 2023 A1-4 (at page 26). A schedule of all these sites will enable consultees to identify and locate them.

- In September 2021 the council unanimously resolved to protect the Green Belt and Bristol’s green spaces. Despite this, around 30 of the 96 sites proposed for residential development are green spaces (nearly 40 hectares) and three areas in our urban Green Belt are proposed to be removed from the Green Belt for development. No new green or open spaces are proposed.

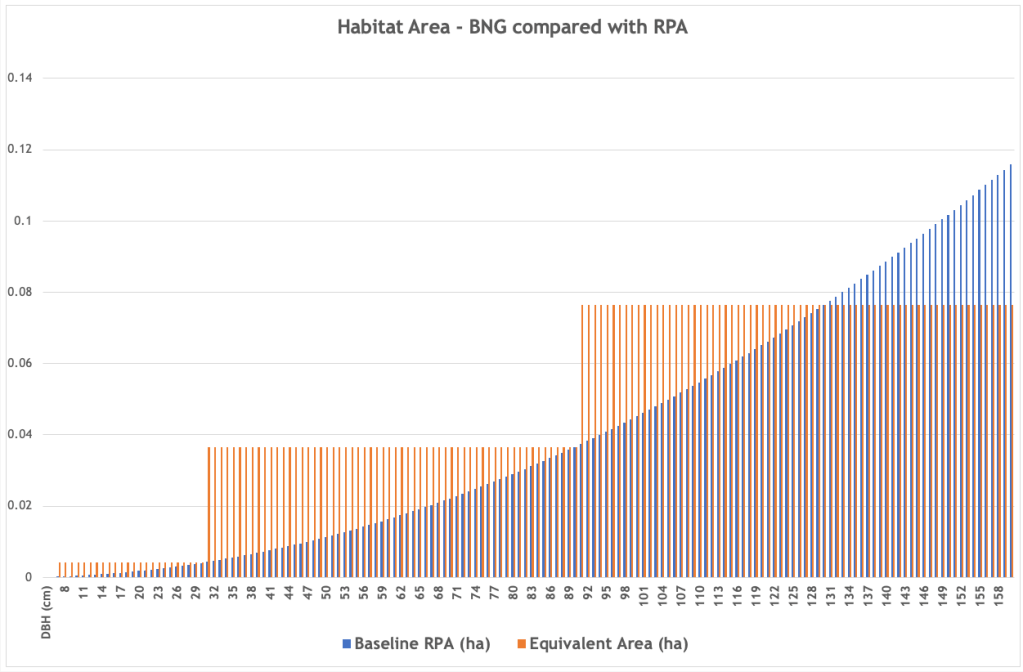

- Proposed policy BG4: Trees is deeply flawed. As currently drafted it will allow developers to offset tree losses by using habitats that are not allowed under BNG 4.0. If allowed this will result in the hollowing out of Bristol’s trees and frustrate the One City plan to increase tree canopy (see Annex A below).

- The proposal that replacement trees ‘should be located as close as possible to the development site’ will still allow developers remove trees to build, because all they need to do is pay compensation for their replacement with no concern for where they are to be planted. This will result in trees and their biodiversity being lost from those areas under greatest development pressure, with any offsite compensation being exported to already green suburbs and creating even greater tree inequalities.

- It is proposed that development which would result in the loss of ancient woodland, or ancient or veteran trees, will not be permitted, but neither Bristol’s known veteran trees nor its 11 ancient woodlands are mapped or expressly protected on the Bristol Local Plan Policies Map.

- No express protection is given for other urban woodlands that are not ancient (woods that have not existed continuously since 1600), are not in a conservation area or are not protected with a TPO.

Our request

Bristol City Council has recently declared both Climate and Ecological Emergencies and resolved to protect our green spaces. The Environment Act 2021 with its still-to-be-published regulations (which will be fully implemented in 2024 together with a proposed new version of the National Planning Policy Framework) will provide even greater environmental protections and the next iteration of the One City Plan aspires to achieve a significant increase of tree canopy. Yet, against all this, the proposed new Local Plan will result in reduced protection for the environment when compared with the current, adopted Local Plan.

In light of this, we ask you to reject the Mayor’s recommendation until the above crucial issues have been addressed and insist that Bristol’s nature does not continue to suffer yet more decades of decline but is properly protected.

The Bristol Tree Forum

24 October 2023

Annex A – Email to BCC Specialist Planning Policy Officer 21 October 2023

Dear Michael,

I see that the latest iteration of the proposed Local Plan has been published. We are examining it and will comment in due course, but we have to express serious concerns about the proposed new wording of Policy BG4: Trees.

We are disappointed that our proposal for BTRS has not been adopted, but we are also very concerned that this paragraph in particular, will provide developers with an opportunity to avoid replacing lost trees at all: ‘Where the tree compensation standard is not already met in full by biodiversity net gain requirements (policy BG3 ‘Achieving biodiversity gains’), for instance because biodiversity net gain requirements do not apply to the development or because biodiversity gains are provided through a different habitat type, development will still be expected to meet the tree compensation standard on-site or off-site through an appropriate legal agreement.‘

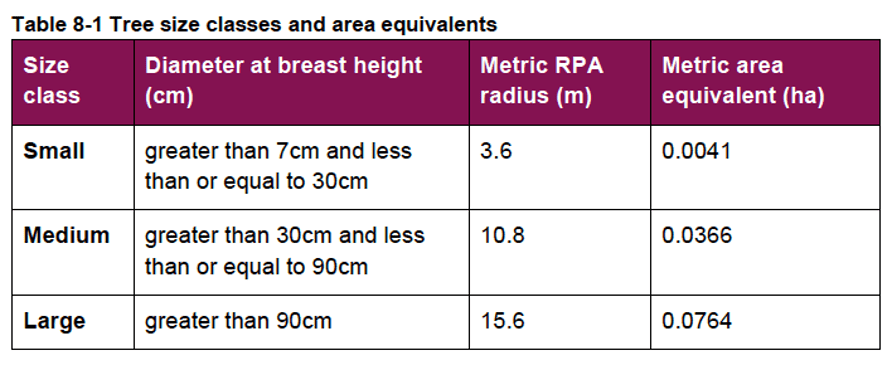

As you know, most trees in an urban environment will be classified as broad Individual tree habitat under BNG 4.0. This broad habitat has only two sub-types – rural and urban – and can only be replaced with the same broad habitat type (Individual tree) or by a more distinctive, High or Very High habitat. This means that other Medium (e.g. most woodland habitats) or Low distinctiveness habitats cannot be used without breaking the BNG 4.0 trading rules – as BG4 currently suggests it can. These High or Very High distinctiveness habitat types are rare, especially in the urban space.

In this case, developers (who will not have the space to create all the Individual tree habitat that BNG 4.0 will demand**) will offer these or Individual tree habitats elsewhere and, because there are no such sites in Bristol, will offset the BNG losses out of the city, resulting in the hollowing out of Bristol’s trees and frustrating the One City plan to increase tree canopy.

We suggest that the proposed wording could also make BG4 unworkable because it is contrary to the BNG 4.0 rules and guidance. We suggest that you delete the words ‘or because biodiversity gains are provided through a different habitat type.’

Can you clarify whether the current Bristol Tree Replacement Standard SPD will remain, please. Is there a list of proposed deprecated policies and SPDs etc. available?

** For example, one small single dwelling development we are looking at which would require five BTRS trees to be planted to replace the three lost, will require 148 BNG 4.0 Small category trees to be planted to achieve a net gain of just 10%. There is not enough room on the site to plant the five BTRS trees, let alone 148.

Subsequent email to BCC Local Plan Team Manager 26 October 2023

Dear Colin,

I am sure you have seen our request to councillors in advance of next week’s Extraordinary Full Council meeting to adopt the Mayor’s recommendation to allow the draft Local Plan to progress to Regulation 19/20 consultation and then to independent examination. If not, I attach a copy.

We Bristolians are as much entitled to know which of their places (and a Local Plan is surely all about place) will not be protected under a new Local Plan as they are to know which will be. Yet, as far as we can see, this information has not been published with the papers laid before Councillors. Please correct me if I am wrong.

For example, we are aware that, under the 2019 document, New Protection for Open Space, it was proposed that Important Open Spaces, currently protected under SADMP DM17, would be replaced with new policies for Local Green Space (LGS) and Reserved Open Space (ROS) (para 2.13). It was obvious then that this would result in a large number of sites, currently protected under this part of DM17, losing this protection because they were not going to be designated as either LGS or ROS nor given any other protections. You will recall that it took us quite some time to get a list of these deprecated sites which we then listed in Appendix A of our response to that consultation. We have no idea whether our representations were considered. From what we have seen, it appears that, if they were, then they were ignored.

It also appears that those other places also given protection under DM17 – Unidentified Open Spacesand Urban landscapes – will also no longer be protected under the new plan, though this has not been expressly stated as far as we can see. It may well be that other place protections have also been quietly dropped and not replaced, but we cannot tell.

This is why we are calling for the following schedules (preferably geolocated) to be published before the next stage of the consultation begins:

- All proposed LGS/ROS designations.

- All sites (places) currently protected under the adopted Local Plan and how they will be protected (or not) under the new LP.

- Currently adopted policies which will be removed – Core, Site Allocation and Development Management Policies (SADMP) and ancillarySupplementary Planning Documents (SPDs) etc. – cross-tabulated to show which of these policies have been transferred to the proposed LP and which have not.

- All sites proposed to be protected under BG2.

- All known veteran and ancient trees and woodland within the city boundaries.

If this information is not provided then it will be impossible for those who wish to respond to the consultation to make an informed decision whether or not to accept what is being proposed and the whole consultation process will, we suggest, be fatally flawed.

I have also heard it suggested that, should Councillors not approve the Mayor’s recommendation then the current adopted Local Plan will lapse and allow developers to proceed as they wish. You know as well as I do that this is not correct. It may well be that, on appeal, developers may argue that Paragraph 11d of the NPPF applies because the Local Plan is out-of-date (Homes England argued this in the recent Brislington Meadows appeal), but this is a very different matter from what I understand has been suggested. Hopefully you will ensure that Councillors are not misled if this is repeated.

I look forward to hearing from you.

[1] R v North & East Devon Health Authority, ex parte Coughlan [2001] QB 213, [2000] 3 All ER 850, 97 LGR 703