The Bristol Tree Replacement Standard (BTRS), adopted a decade ago, provides a mechanism for calculating the number of replacements for any trees that are removed for developments. It was ground-breaking in its time as it, typically, required more than 1:1 replacement of trees lost to development.

The presumption when considering any development involving established trees should always be that trees will be retained. The application of BTRS should only ever be a last resort. It should not be the default choice which it seems to have become.

The starting point for any decision on whether to remove trees (or any other green asset for that matter) is the Mitigation Hierarchy. Paragraph 180 a) of the National Planning Policy Framework sets it out as follows:

If significant harm to biodiversity resulting from a development cannot be avoided (through locating on an alternative site with less harmful impacts), adequately mitigated, or, as a last resort, compensated for, then planning permission should be refused.[1]

BTRS is and should always be ‘a last resort’. This is reflected in the Bristol Core Strategy, policy BCS9 adopts this approach and states that:

Individual green assets should be retained wherever possible and integrated into new developments.[2]

However, with the development of a new Local Plan for Bristol, we believe that the time has come for BTRS to be revised to reflect our changing understanding of the vital importance of urban trees to Bristol in the years since the final part (SADMP) of the Local Plan was adopted in 2014.

In addition, Bristol has adopted Climate and Ecological Emergency Declarations so a new BTRS will be an important part of implementing these declarations. Nationally, the Environment Act 2021 (EA 2021) will come force later this year. This will require nearly all developments to achieve a Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) of at least 10%. Our proposal provides a mechanism for complying with this new requirement and so aligns BTRS with the BNG provisions of the EA 2021.

Background

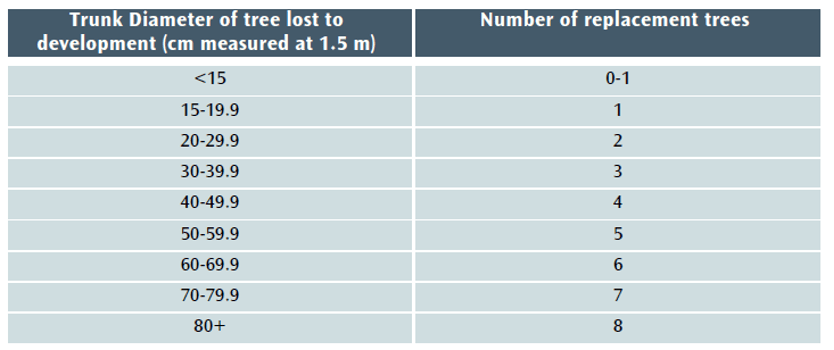

Under current policy – BCS9 and DM17[3] – trees lost to development must be replaced using this table:

Table 1 The Current DM17/BTRS replacement tree table.

However, when the balance of EA 2021 takes effect, the current version of BTRS will not, in most cases, be sufficient to achieve the 10% BNG minimum that will be required for nearly all developments. A new section 90A will be added to the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and set out the level of BNG required (see Schedule 14 of EA 2021).

The Local Government Association says of BNG that it:

…delivers measurable improvements for biodiversity by creating or enhancing habitats in association with development. Biodiversity net gain can be achieved on-site, off-site or through a combination of on-site and off-site measures.[4]

GOV.UK says of the Biodiversity Metric that:

where a development has an impact on biodiversity, it will ensure that the development is delivered in a way which helps to restore any biodiversity loss and seeks to deliver thriving natural spaces for local communities.[5]

This aligns perfectly with Bristol’s recent declarations of climate and ecological emergencies and with the aspirations of the Ecological Emergency Action Plan,[6] which recognises that a BNG of at least 10% net gain will become mandatory for housing and development and acknowledges that:

These strategies [the Local Nature Recovery Strategies] will guide smooth and effective delivery of Biodiversity Net…

Our proposed new BTRS model

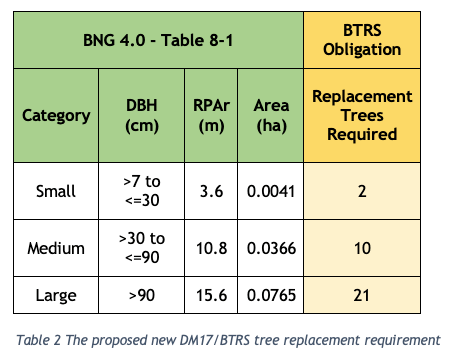

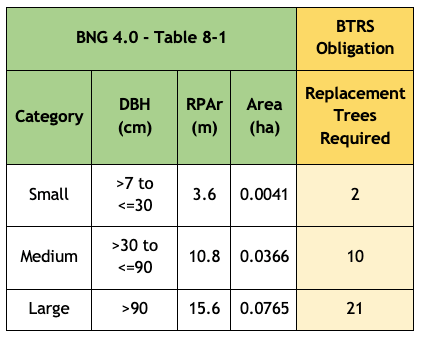

We propose that the Bristol Tree Replacement Standard be amended to reflect the requirements of the EA 2021 and BNG 4.0 and that the BTRS table (Table 1 above) be replaced with Table 2 below:

The Replacement Trees Required number is based on the habitat area of each of the three BNG 4.0 tree category sizes (Table 8-1 below) divided by the area habitat of one BNG 4.0 Small category tree (see section 3 below) plus a 10% net gain. This is rounded up to the nearest whole number – you can’t plant a fraction of a tree.

The reasoning for our proposal is set out below.

Applying the Biodiversity Metric to Urban trees

The most recent Biodiversity Metric (BNG 4.0) published by Natural England this April, defines trees in urban spaces as Individual trees called Urban tree habitats. The User Guide states that:

Individual trees may be classed as ‘urban’ or ‘rural’. Typically, urban trees will be bound by (or near) hardstanding and rural trees are likely to be found in open countryside. The assessor should consider the degree of ‘urbanisation’ of habitats around the tree and assign the best fit for the location.

Individual trees may also be found in groups or stands (with overlapping canopies) within and around the perimeter of urban land. This includes those along urban streets, highways, railways and canals, and also former field boundary trees incorporated into developments. For example, if groups of trees within the urban environment do not match the descriptions for woodland, they may be assessed as a block of individual urban trees.

Calculating Individual trees habitat

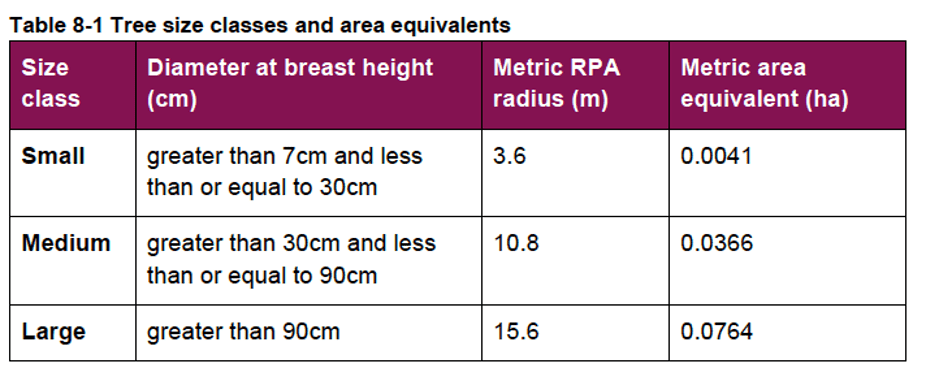

Table 8-1 in the BNG 4.0 user guide is used to calculate the ‘area equivalent’ of individual trees:

Note that the tree’s stem diameter will still need to be ascertained using BS:5837 2012,[7] and that any tree with a stem diameter (DBH) 7 mm or more and of whatever quality (even a dead tree, which offers its own habitat benefits) is included. Under the current DM17/BTRS requirement, trees with a DBH smaller than 150 mm are excluded, as are BS:5837 2012 category “U” trees. This will no longer be the case.

The Rule 3 of the BNG User guide makes it clear that like-for-like replacement is most often required, so that lost Individual trees (which have Medium distinctiveness) are to be replaced by Individual trees rather than by other habitat types of the same distinctiveness.[8]

Forecasting the post-development habitat area of new Individual trees

The BNG 4.0 User Guide provides this guidance:

8.3.13. Size classes for newly planted trees should be classified by a projected size relevant to the project timeframe.

• most newly planted street trees should be categorised as ‘small’

• evidence is required to justify the input of larger size classes

8.3.14. When estimating the size of planted trees consideration should be given to growth rate, which is determined by a wide range of factors, including tree vigour, geography, soil conditions, sunlight, precipitation levels and temperature.

8.3.15. Do not record natural size increases of pre-existing baseline trees within post-development calculations.

Our calculations are based on ‘small’ category replacement trees being planted.

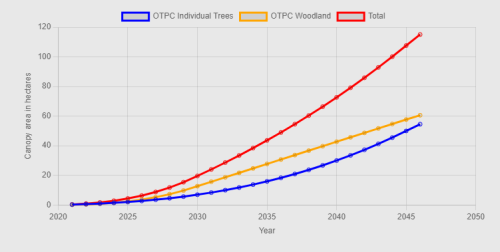

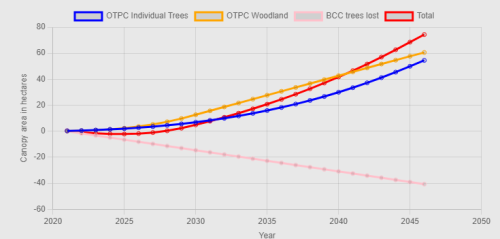

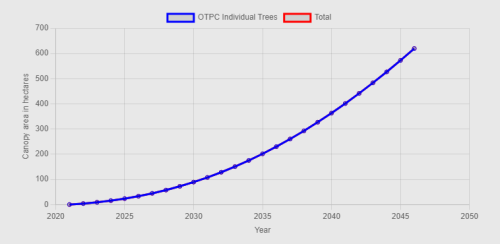

The likely impact of this policy change

We have analysed tree data for 1,038 surveyed trees taken from a sample of BS:5837 2012 tree surveys submitted in support of previous planning applications. Most of the trees in this sample, 61%, fall within the BNG 4.0 Small range, 38% are within the Medium range, with the balance, 1%, being categorised as Large.

Table 4 below sets out the likely impact of the proposed changes to BTRS. It assumes that all these trees were removed (though that was not the case for all the planning applications we sampled):

The spreadsheet setting out the basis of our calculations can be downloaded here – RPA Table BNG 4.0 8-1 table Comparison.

Our proposed changes to BTRS are set out in Appendix 1.

A copy of this article is available here.

Appendix 1 – Our proposed changes to BTRS

See the Planning Obligations Supplementary Planning Document at page 20.

Trees – Policy Background

The justification for requiring obligations in respect of new or compensatory tree planting is set out in the Environment Act 2021, Policies BCS9 and BCS11 of the Council’s Core Strategy and in DM 17 of the Council’s Site Allocations and Development Management Policies.[9]

Trigger for Obligation

Obligations in respect of trees will be required where there is an obligation under the Environment Act 2021 to compensate for the loss of biodiversity when Urban tree habitat is lost as a result of development.

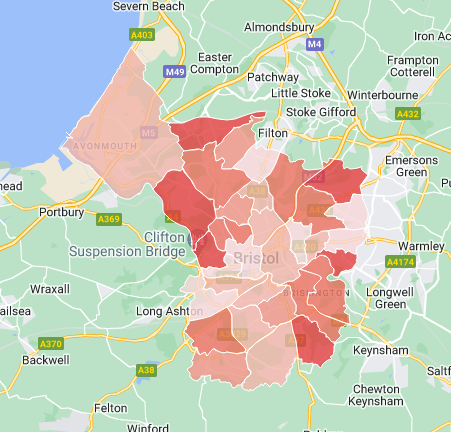

Any offsite Urban tree habitat creation will take place in sites which are either on open ground or in areas of hard standing such as pavements and are located as close as possible to the site of the lost tree.

Where planting will take place directly into open ground, the contribution will be lower than where the planting is in an area of hard standing. This is because of the need to plant trees located in areas of hard standing in an engineered tree pit.

All tree planting on public land will be undertaken by the council to ensure a consistent approach and level of quality, and to reduce the likelihood of new tree stock failing to survive.

Level of Contribution

The contribution covers the cost of providing the tree pit (where appropriate), purchasing, planting, protecting, establishing and initially maintaining the new tree. The level of contribution per tree is as follows:

- Tree in open ground (no tree pit required) £765.21

- Tree in hard standing (tree pit required) £3,318.88[10]

The ‘open ground’ figure will apply where a development results in the loss of Council-owned trees planted in open ground. In these cases, the Council will undertake replacement tree planting in the nearest appropriate area of public open space.

In all other cases, the level of offsite compensation required will be based on the nature (in open ground or in hard standing) of the specific site which will has been identified by the developer and is approved by the Council during the planning approval process. In the absence of any such agreement, the level of contribution will be for a tree in hard standing.

The calculation of the habitat required to compensate for loss of Urban trees is set out in Table 8-1 of the Biodiversity Metric (BNG), published by Natural England. This may be updated as newer versions of BNG become mandatory under the Environment Act 2021.

The following table will be used when calculating the level of contribution required by this obligation:

[1] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1005759/NPPF_July_2021.pdf

[2] https://www.bristol.gov.uk/files/documents/64-core-strategy-web-pdf-low-res-with-links/file at page 74.

[3] https://www.bristol.gov.uk/files/documents/5718-cd5-2-brislington-meadows-site-allocations-and-development-management-policies/file page 36.

[4] https://www.local.gov.uk/pas/topics/environment/biodiversity-net-gain.

[5] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/biodiversity-30-metric-launched-in-new-sustainable-development-toolkit.

[6] https://www.bristol.gov.uk/documents/20182/5572361/Ecological_Emergency_Action_Plan.pdf/2e98b357-5e7c-d926-3a52-bf602e01d44c?t=1630497102530.

[7] https://knowledge.bsigroup.com/products/trees-in-relation-to-design-demolition-and-construction-recommendations/standard

[8] Table 3-2 Trading rules (Rule 3) to compensate for losses. Any habitat from a higher distinctiveness band (from any broad habitat type) may also be used.

[9] These references may need to be changed to reflect any replacement policies adopted with the new Local Plan.

[10] These values should be updated to the current rates applicable at the time of adoption. The current indexed rates as of May 2023 are £1,143.15 & £4,958.07 respectively.