Our Tree Giveaway is now closed- All the trees on offer are now taken.

Perhaps one of the most significant things we can do to help protect our future environment, promote nature and make the world a better place for generations to come is to plant a tree. It may be that trees we plant today will continue to provide benefits for the environment, wildlife and people, for hundreds of years to come.

Planting trees is still the most effective and widespread means of removing CO2 from the atmosphere. For instance, a single mature oak tree is the equivalent of 18 tonnes of CO2 or 16 passenger return transatlantic flights. However, it is in our cities that trees provide the greatest benefits; cleaning our air, reducing flooding, reducing traffic noise, improving our physical and mental health, and, crucially, reducing temperatures during heat waves.

During heat waves, that are predicted to increase in both severity and frequency, the “heat island” effect can raise temperatures in cities by as much as an additional 12C over that found in surrounding rural areas. Trees can greatly reduce this effect, partly through shade but also by actively cooling the air by drawing up water from deep underground, which evaporates from the leaves… a process called evapotranspiration. According to the US Department of Agriculture, this cooling effect is the equivalent to 10 room sized air con units for each mature tree.

Thus, trees are a crucial, but often ignored, element in increasing our resilience to climate change.

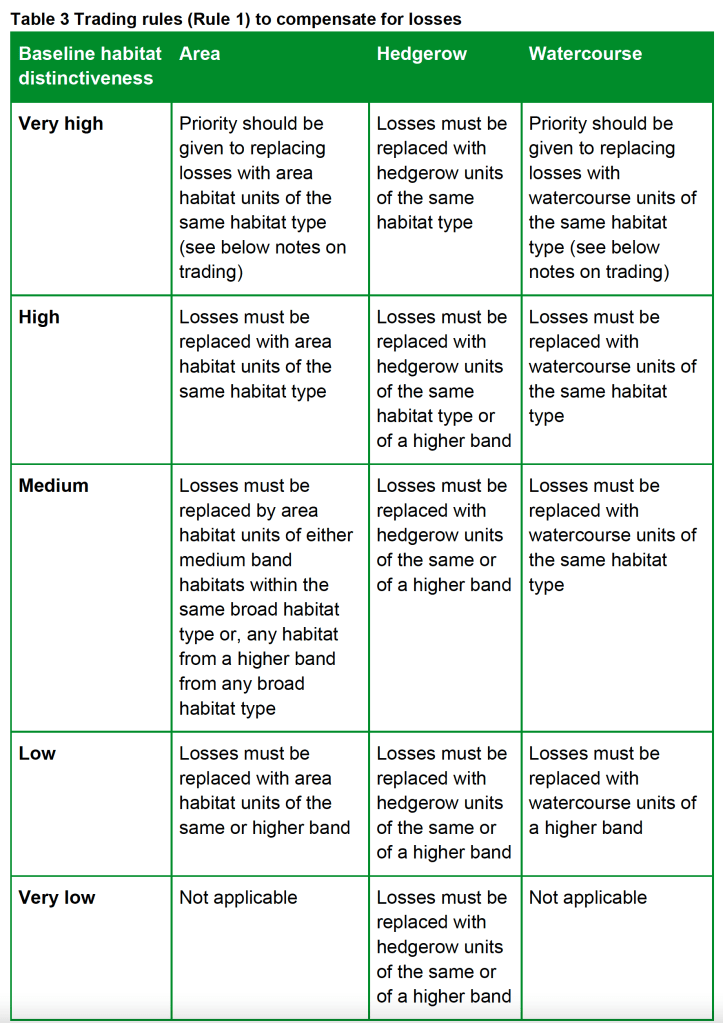

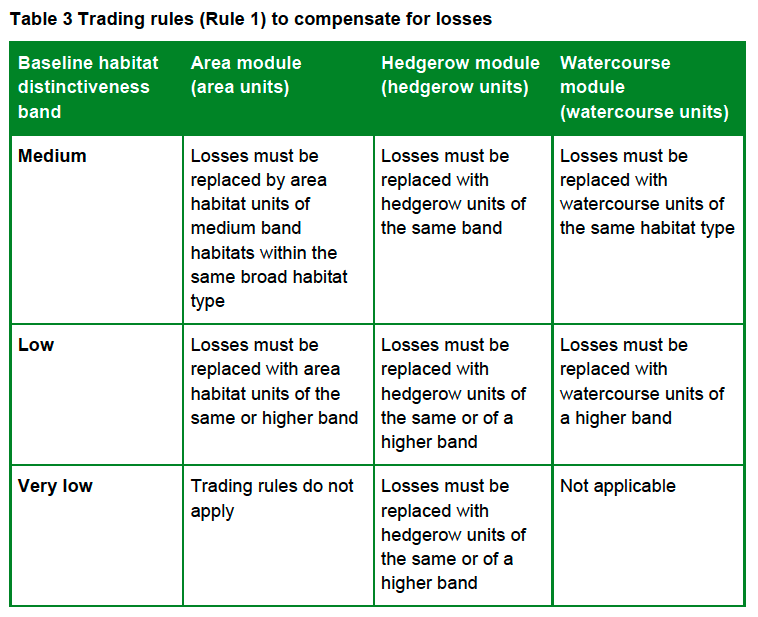

The UK is one of the most nature depleted countries in the world, and have lost nearly 70% of our biodiversity since the industrial revolution. Trees are vital in supporting biodiversity. With national legislation now allowing around 60% of development sites to be exempt from the need to replace lost biodiversity, and this biodiversity permitted to be replaced anywhere in the country, our city trees are under greater threat than ever before. Furthermore, the proposed new Local Plan, which sets planning policy for the next decade or more, appears to reduce protection for Bristol’s green spaces, allowing these to be built upon.

Therefore, increasingly, it is up to us to protect nature, and what better way of doing this than to plant a tree?

What is the Bristol Tree Forum doing to help?

It is said that the best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago, and the second best time is now.

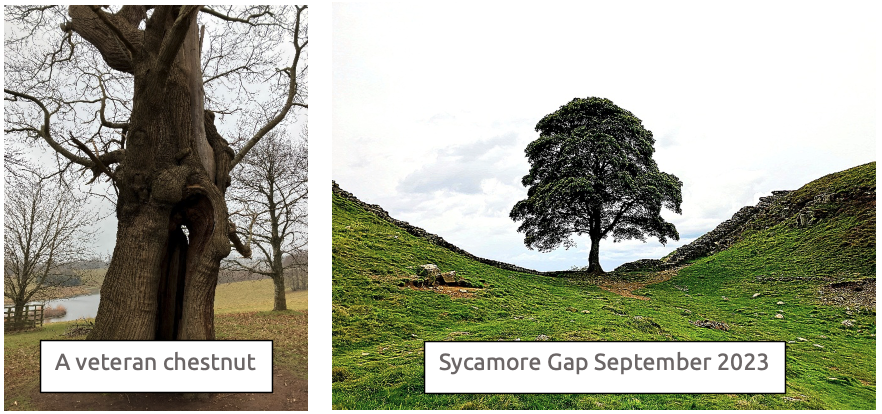

Unfortunately, important mature trees are constantly being lost to development, damage and disease. Though these might easily be replaced by new trees, what is less easy is replacing the decades or even centuries that the tree has taken to grow, the carbon that the tree has sequestered, the ecosystems the tree supports and all of the other benefits trees provide. For these reasons, much of the work of the Bristol Tree Forum focuses on protecting our existing trees. These efforts are particularly crucial in the urban environment where our trees are under the greatest threat.

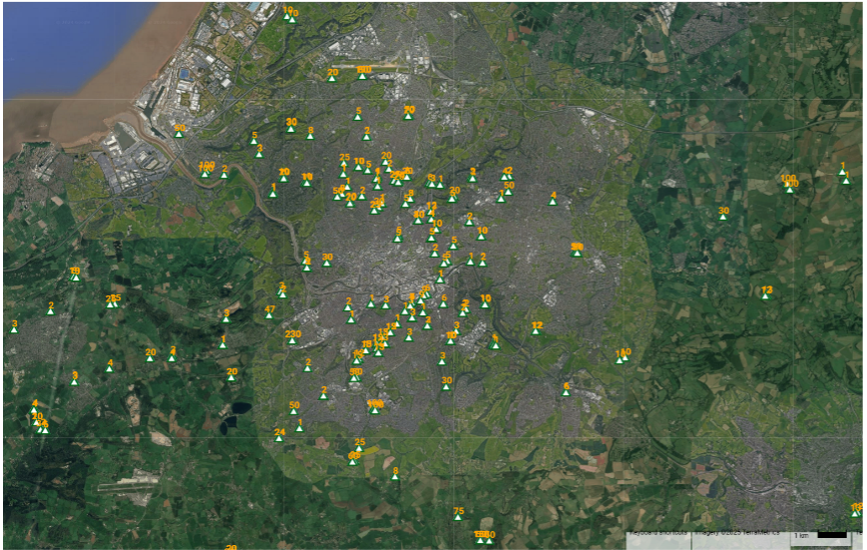

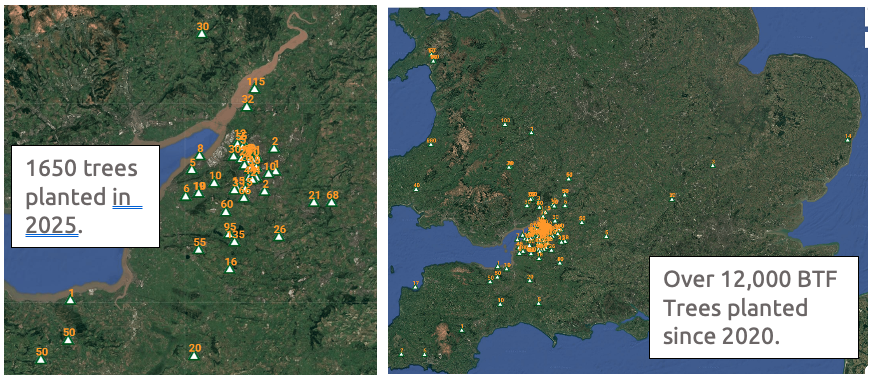

However, as well as advocating the retention of life-saving trees in our city, Bristol Tree Forum have been encouraging new tree planting by holding an annual tree giveaway since 2020; the ancient trees of the future are being planted today! Most of Bristol’s trees are sited in private land and gardens, so the trees we have are mostly thanks to the efforts of Bristol residents, and it is those residents we must look to if we want to increase our tree canopy.

Over the last five years, we have given away over 12,000 trees, with species as diverse as English and sessile oak, downy birch, silver birch, grey birch, alder, alder buckthorn, rowan, Scots pine, sweet chestnut, sycamore, spindle, wild cherry, apple, pear and plum.

This year’s Tree Giveaway has been made possible by the generous support of Maelor Forest Nurseries, based on the Welsh borders.

Thanks to Maelor, we are able to offer a variety of species of different mature stature and preferred habitats. This year we are giving away:

English oak (Quercus robur), hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna), beech (Fagus sylvatica), hornbeam (Carpinus betulus), grey alder (Alnus incana), and crab apple (Malus sylvestris).

We will get delivery of the saplings in mid to late February, when the trees can be collected from a site in Redland, Bristol.

The small saplings, or whips, come bare-rooted (i.e. out of the soil) and need to be planted as soon as possible after collection, although the viability of the trees over winter can be extended by storing the trees with the roots covered in damp soil.

To order your tree saplings:

The Tree Giveaway is now closed- All the trees on offer are now taken.

Email: xxx with the subject “Tree Giveaway” and tell us:

- Your name and email.

- Your post code – for an approximate location of the planned planting sites, so that we can include these on our map.

- How many of each species you would like – English oak, hawthorn, beech, hornbeam, grey alder, or crab apple.

We will email you to organise a collection date and time in February.