Planting a tree is, perhaps, one of the most significant things we can do to help protect our future environment, promote nature and make the world a better place for the generations to come. The trees we plant today will continue to provide benefits for the environment, wildlife and people, for hundreds of years.

A veteran chestnut

We all know the value of trees in sequestering carbon, and they still represent the most effective and widespread means of removing CO2 from the atmosphere. For instance, a single mature oak tree is the equivalent of 18 tonnes of CO2 or 16 passenger return transatlantic flights. However, it is in our cities that trees provide the greatest benefits; cleaning our air, reducing flooding, improving our physical and mental health, and, crucially, reducing temperatures during heat waves.

Our cities suffer additional problems during heat waves, with all of the concrete and tarmac absorbing a lot of energy from the cooling sun and releasing it as heat. This “heat island” effect can raise temperatures by as much as an additional 12 degree centigrade. Trees can greatly reduce, or even eliminate, this effect, partly through shade but also actively cooling the air by drawing up water from deep underground, which evaporates from the leaves… a process called evapotranspiration. According to the US Department of Agriculture, this cooling effect is the equivalent to 10 room sized air con units for each mature tree. This cooling greatly enhances our resilience to the dangerous heat waves that are predicted to increase in severity and frequency.

A veteran Beech

A stand of Silver birch

Also, Trees improve air quality by absorbing both gaseous (e.g., NO2) and particulate pollution. They reduce traffic noise and flooding and improve physical and mental wellbeing.

Thus, trees are a crucial, but often ignored, element in increasing our resilience to climate change.

What are the Bristol Tree Forum doing to help?

It is said that the best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago, and the second-best time is now.

Unfortunately, important mature trees are constantly being lost to development, damage and disease. Though these might easily be replaced by new trees, what is less easy is replacing the decades or even centuries that the tree has taken to grow, the carbon that the tree has sequestered, the ecosystems the tree supports and all of the other benefits trees provide. For these reasons, most of the work of the Bristol Tree Forum focuses on protecting our existing trees. These efforts are particularly crucial in the urban environment where our trees are under the greatest threat.

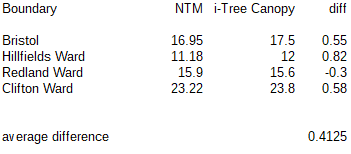

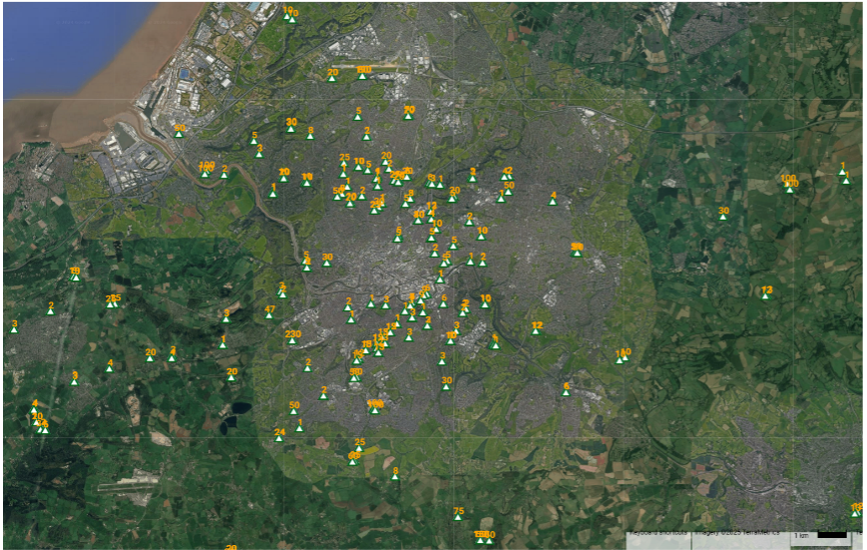

However, as well as advocating the retention of life-saving trees in our city, Bristol Tree Forum have been encouraging new tree planting by holding an annual tree giveaway since 2020; the ancient trees of the future are being planted today! Most of Bristol’s trees are sited in private land and gardens, so the trees we have are mostly thanks to the efforts of Bristol residents, and it is those residents we must look to if we want to increase our tree canopy.

Over the last four years, we have given away around 10,600 trees, with species as diverse as English and Sessile oak, Downy birch, Silver birch, Grey birch, Alder, Alder buckthorn, Rowan, Scots pine, Sweet chestnut, Sycamore, Spindle, Wild cherry, apple, pear and plum.

Trees given away in 2022 / 2023

Red oak sapling

This year’s Tree Giveaway has been made possible by the generous support of Maelor Forest Nurseries, based on the Welsh borders, and Protect Earth whose aim is to plant, and help people plant, as many trees as possible in the UK to help mitigate the climate crisis.

Thanks to Maelor, we are able to offer a variety of species with a wide range of sizes and preferred habitats, including Pedunculate (English) oak, Red oak, Sweet chestnut, Silver birch, Sycamore, Hawthorn, Beech, Hornbeam, Wild cherry, Alder, Red alder, Field maple and Norway maple.

Trees can be ordered using the form below

We will get delivery of trees in February, when the trees can be collected from a site in Redland, Bristol. We will email you when they are ready.

The saplings come bare-rooted (i.e. out of the soil) and will need to be planted as soon as possible after collection, although the viability of the trees over winter can be extended by storing the trees with the roots covered in damp soil.

The form below is to find out who would like to have saplings for planting, which species, how many and where you plan to plant them.

Please provide your email so we can contact you organise collection of the trees. Your contact details will be kept private and will not be used for any other purpose than to process your request.

Our Giveaway offer has now been filled.

Thanks for all your support.