The West of England Mayoral Combined Authority (WECA as was) Local Nature Recovery Strategy was published to much fanfare last November. Defra’s blog, Kickstarting local nature recovery: a new strategy for the West of England, hailed it as the first in the country.

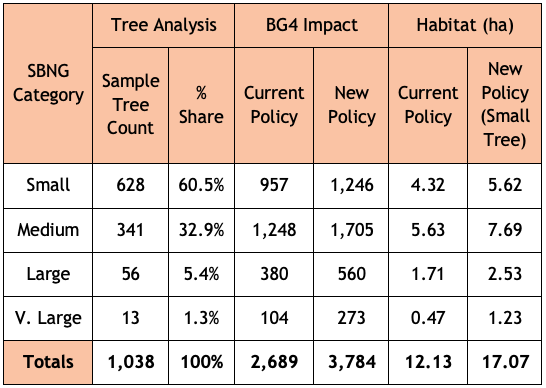

The LNRS is a locally led and evidence-based strategy which aims to target action and nature investment where it’s most needed. We’re told that the strategy will also focus on biodiversity net gain by increasing the strategic significance of specific habitats. However, it is hard to imagine how the LNRS will help to enhance biodiversity net gain in most, if not all, potential development sites in the city.

We might have been better off, at least as far as the application of biodiversity net gain to new development is concerned, by asking the LPA to specify alternative documents (such as those listed at the end of this article) for assigning strategic significance instead.

The issue

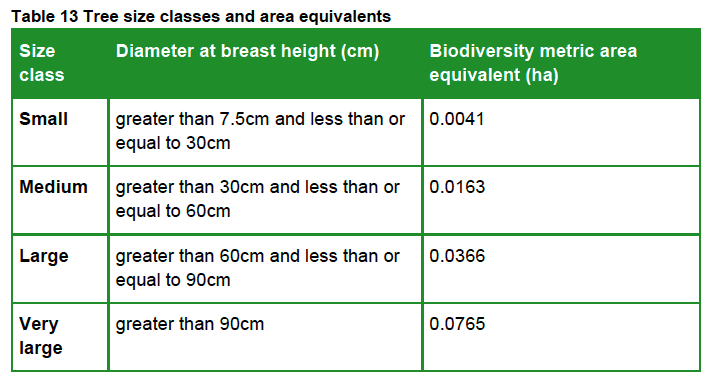

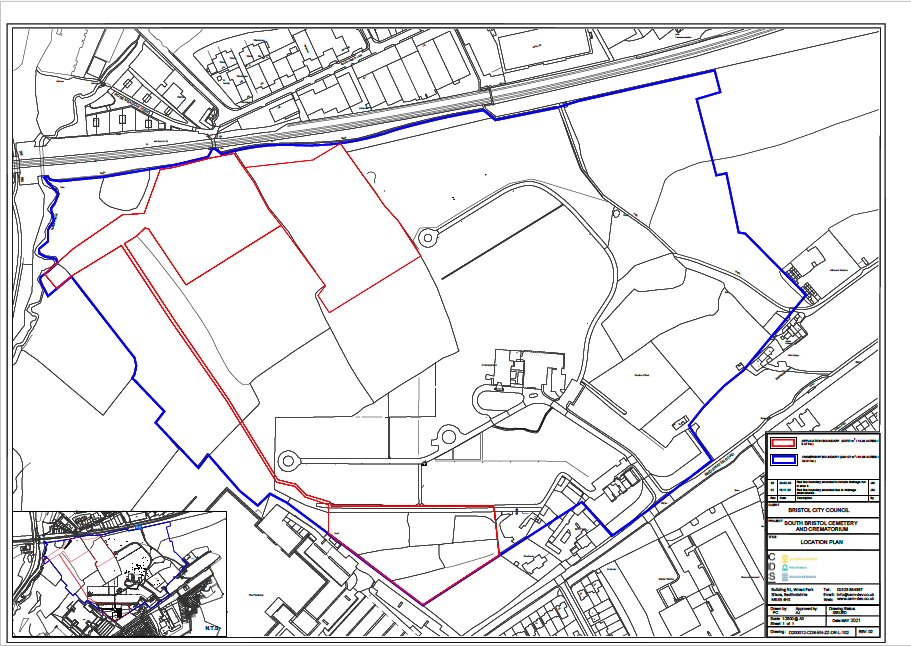

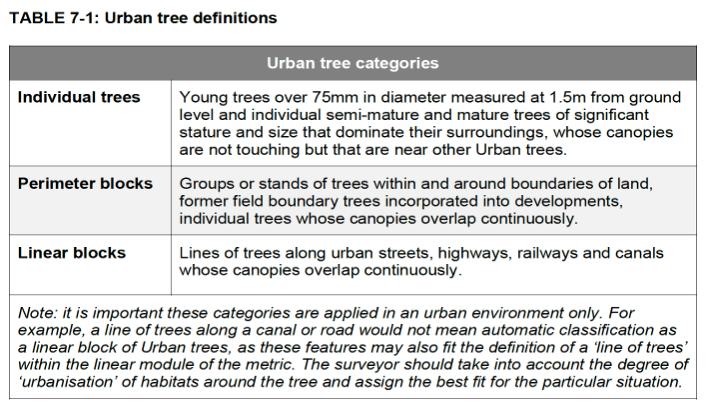

When calculating the impact of a proposed development on biodiversity, one factor taken into account is the strategic significance of any habitat found on a focus area for nature recovery site (coloured purple in the map above). If strategically significant habitats are created or enhanced, then their strategic significance is set to High in the Statutory Metric calculator tool and a 15% uplift to the calculation of its value is applied. Subject to which of the six LNRS areas is being considered, these are the strategically significant habitats in the city:

- Ditches

- Ecologically valuable lines of trees

- Ecologically valuable lines of trees – associated with bank or ditch

- Grassland – Floodplain wetland mosaic and CFGM

- Grassland – Lowland calcareous grassland

- Grassland – Lowland meadows

- Heathland and shrub – Mixed scrub

- Heathland and shrub – Willow scrub

- Individual urban or rural trees

- Lakes – Ponds (priority habitat)

- Priority habitat (on the River Avon and the Riparian buffers)

- Species-rich native hedgerow with trees – associated with bank or ditch

- Species-rich native hedgerow with trees

- Species-rich native hedgerows – associated with bank or ditch

- Species-rich native hedgerows

- Urban – Open mosaic habitats on previously developed land

- Urban – Biodiverse green roofs

- Woodland and forest – Lowland beech and yew woodland

- Woodland and forest – Lowland mixed deciduous woodland

- Woodland and forest – Other woodland; broadleaved

- Woodland and forest – Wood-pasture and parkland

However, a detailed examination of the LNRS map reveals that not all parks and green spaces have been designated as focus area for nature recovery sites. It’s only those which are in one or both of the following:

- a location where they can make a greater contribution to ecological networks

- deprived areas with a lack of access to nature.

These designations were based on Bristol’s previous work on ecological networks within the city and where wildlife-friendly interventions are most likely to be feasible. This means that the existence, creation or enhancement of these special habitats outside these areas will not attract the 15% strategic significance uplift.

The BNG requirements

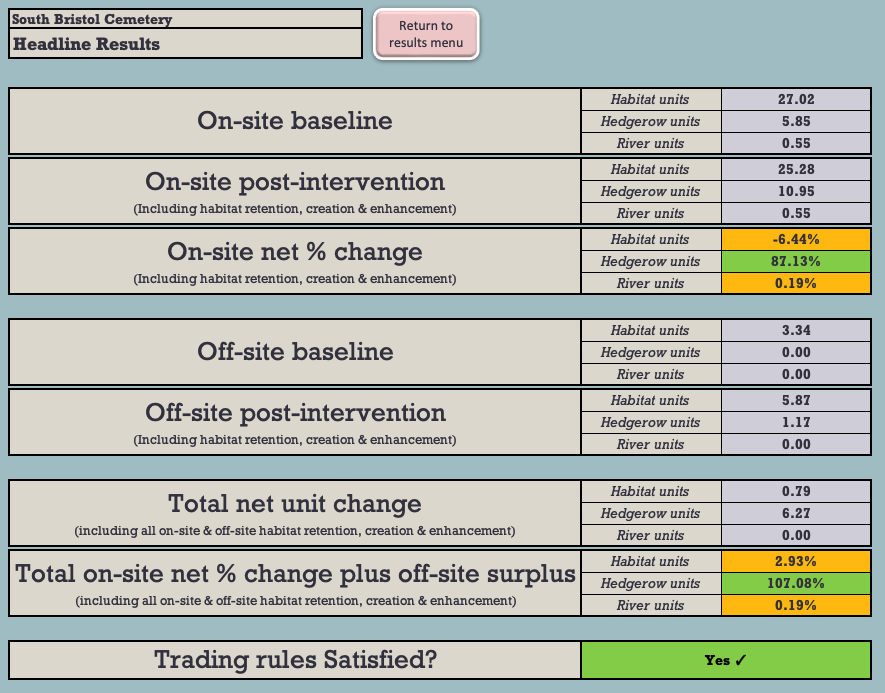

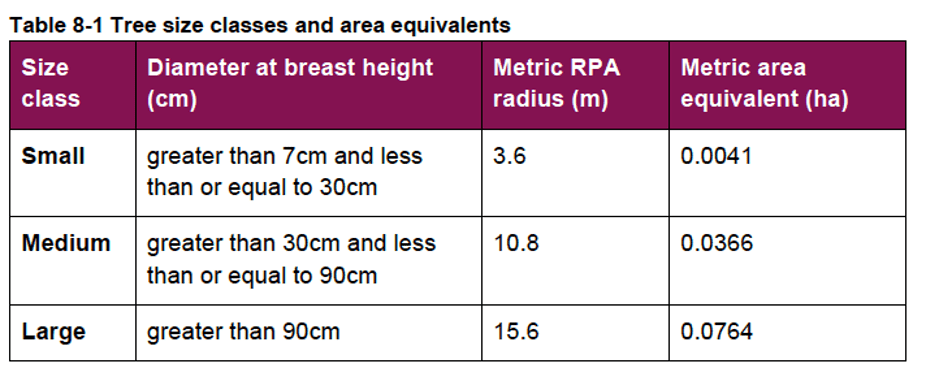

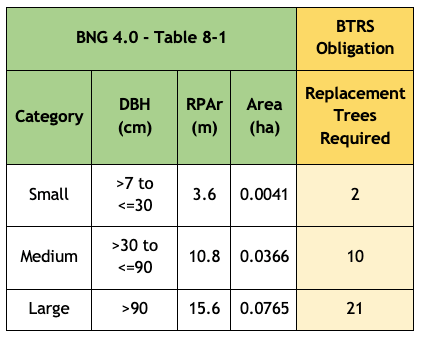

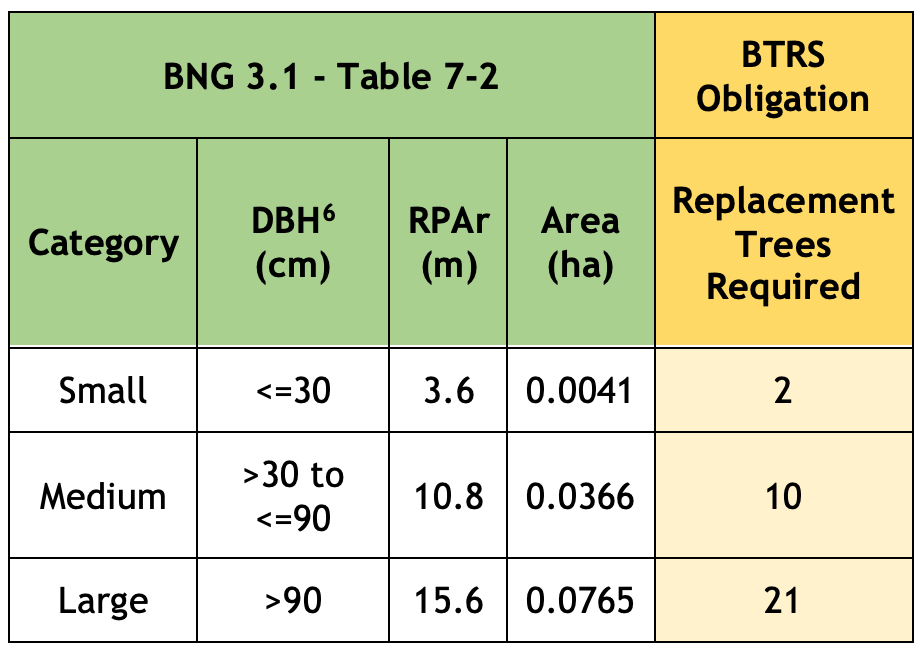

The now compulsory Statutory Metric Guide, used for calculating Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG), advises (at page 27) that: ‘Strategic significance is the local significance of the habitat based on its location and habitat type. You should assess each individual habitat parcel, both at baseline and at post-intervention, for on-site and off-site.’

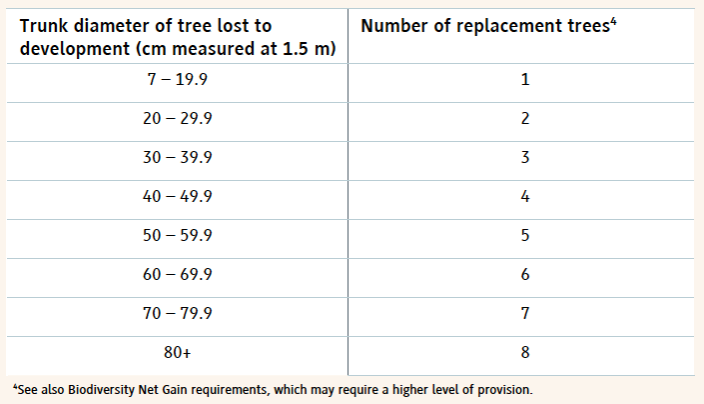

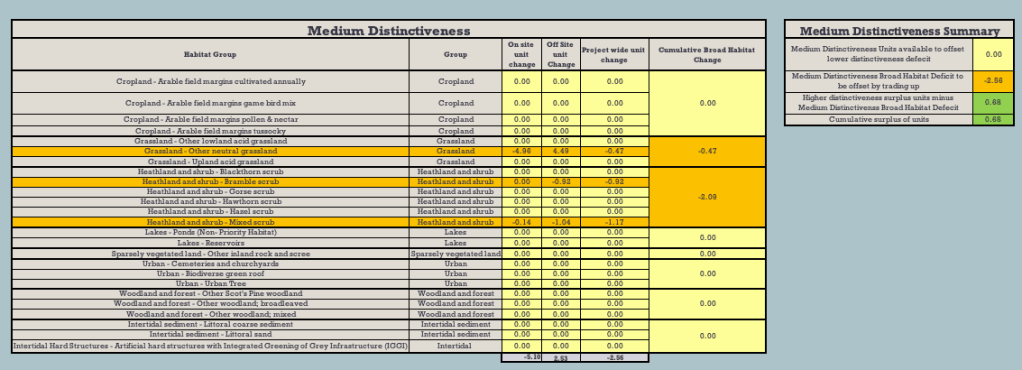

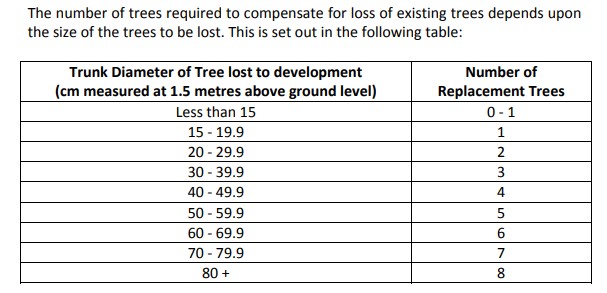

If the LPA has adopted an LNRS then only the High or Low strategic significance multipliers can be used (High – formally identified in local strategy = 1.15. Low – area compensation not in local strategy = 1). If it has not adopted an LNRS, then the Medium strategic significance multiplier may also be used (Location ecologically desirable but not in local strategy = 1.10).

Where an LPA has adopted an LNRS, all those sites which have not been identified as a focus area for nature recovery site will be designated as having Low strategic significance and so attract no uplift, even if they’ve been identified as important habitats in the Local Plan or in another strategic document adopted by the Council. These documents (used where an LPA has not adopted an LNRS) can include:

- Draft Local Nature Recovery Strategies

- Local Plans and Neighbourhood Plans

- Local Planning Authority Local Ecological Networks

- Parks and Green Spaces Strategies

- Tree and Woodland Strategies

- Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plans

- Biodiversity Action Plans

- Species conservation and protected sites strategies

- Green Infrastructure Strategies

- River Basin Management Plans

- Catchment Plans and Catchment Planning Systems

- Shoreline management plans

- Estuary Strategies

Baseline habitats cannot be uplifted

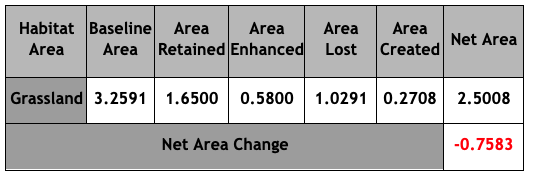

Despite the BNG strategic significance guidance, Defra has stated that LNRS designations only apply to the creation or enhancement of post-development biodiversity mitigation habitats. They don’t apply if these habitats – called the baseline habitats – are found on the site before development begins.

This means that the 15% strategic significance uplift can only be applied where offsite biodiversity mitigation is being delivered in a focus area for nature recovery site. If these habitats are being delivered elsewhere, the uplift may not be applied.

However, even if the baseline habitats were included, it is unlikely to make any difference This is because the focus area for nature recovery sites identified in Bristol are, for the most part, located in public parks or green spaces, on river banks, in riparian buffers or on railway margins, none of which are likely ever to be developed or, in many cases, used to offset habitat lost to development elsewhere.

So far, no announcement has been made as to whether any of Bristol’s focus area for nature recovery sites will be made available for offsite habitat mitigation and the proposed new Local Plan does not commit to using these sites for this purpose.

This, combined with the challenge of finding LNRS suitable for offsite habitat mitigation, registering them as biodiversity gain sites and then managing them, effectively, in perpetuity, suggests that few feasible LNRS sites will be found, especially as many sites are also in demand for public access for recreation.

We set out the process used to assess the strategic significance of habitats on our blog, Assessing habitat parcels: strategic significance explained.